Charles Helfenstein’s book on the making of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (abbreviated as OHMSS henceforth for the sake of brevity) stands as the definitive resource for fans who want to know more about the 1969 film. While the book contains a great amount of fascinating rare photos, it is the scholarly written text within that provides some of the most comprehensive and exhaustive accounts ever written regarding this film. While it may appear on the surface to be a coffee table book, it’s actually a great resource for Bond fans to digest.

Helfenstein begins with a chapter regarding Ian Fleming’s writing of the novel which I found incredibly useful for my previous blog post concerning Fleming’s original book. Here, it is revealed that Fleming actually began his research with Robin Mirrlees from the College of Arms a few years before conceiving of the OHMSS novel specifically desiring a basis to give Bond a Scottish ancestral background prior to Sean Connery getting the role. While some in the Bond fan community believe that Connery had been the reason for Fleming’s revelation of Bond’s Scottish origin, Helfenstein makes a strong case that Fleming had wanted to tap into his own Scottish ancestral origins years before Connery had come into the picture. While Mirlees’ research failed to yield any results confirming a Scottish background for Bond, he did provide a motto for the Bond family crest that would forever hold significance to the Bond franchise and provide a credo for Fleming’s characterization which fit Bond to a tea: “The World is Not Enough.”

Helfenstein’s research revealed Fleming’s original title for the book to be “The Belles of Hell” after wartime song sung by soldiers in World War I. There’s also the fact that Fleming had based Piz Gloria, which would serve as Blofeld’s headquarters, on 3 sources that Fleming no doubt obtained some information about during his holiday skiing vacations at St. Moritz. These were: The Sphinx Observatory at Jungfraugoch in the Swiss Alps, a location in the Bavarian Alps that was known as “Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest” during the war, and a sporting club in the Austrian Alps called Schloss Mittersill. We also learn that OHMSS was the first and only time that Fleming released a signed limited edition of the novel coinciding with the release of the standard edition with its Richard Chopping artwork procured for the dust jacket. The special limited edition was released in a clear plastic dust jacket, gilt lettering on the spine, a color portrait of Fleming with the edition’s “copy number” hand written in black ink, and Ian Fleming’s hand written signature in blue ink. Very few of these limited editions survive and one of Fleming’s personal copies remains at the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Helfenstein goes on to say, “The amount of effort and detail that went into this edition makes it evident that Ian Fleming was quite proud of the novel.” It is indeed hard to disagree with that sentiment as the novel clearly stands apart as a masterpiece within Fleming’s literary Bond canon.

The bulk of Helfenstein’s book is dedicated to the 1969 film adaptation of OHMSS starring first time actor George Lazenby as James Bond. Screenwriter, Richard Maibaum, had already achieved a great deal of success adapting 4 of the 5 previous Bond films for EON starring Sean Connery. It would seem that as early as 1964, Maibaum was eager to adapt OHMSS as the first film treatment from June of that year suggests. The early film treatment contains a different spin on elements that would go on to be used frequently within the Bond film franchise – one being the fake death. Only this time, instead of the filmmakers faking Bond’s death, it would be Blofeld who would fake his death. Also present in this earliest imagining of the film is Bond’s second secretary from the novels Mary Goodnight, who took over secretarial duties for Loelia Ponsonby who had served as Bond’s secretary for the previous novels. In the scene with M.’s secretary, Miss Moneypenny, she refuses to accept Bond’s resignation jokingly referring to her wager in the office pool as to who would get to bed Mary Goodnight first – a prospect that is unashamedly politically incorrect. Further early treatments and screenplays indicate that Maibaum had been eager to include a scene where Bond would befriend a chimp at Blofeld’s zoo. Once Bond’s identity was discovered, Blofeld would have his men lock Bond with the chimp, and the chimp would assist in Bond’s escape. In some incarnations of these early film treatments, Bond would actually make a point of rescuing the chimp from captivity during the climatic attack on Piz Gloria in the final act of the film. Maibaum had even wanted to recruit Gert Frobe, who had played the villain Goldfinger in the 1964 Bond film to play Blofeld as Goldfinger’s twin brother.

Thankfully, none of those outlandish ideas ever made it to the final shooting script, but here Helfenstein paints a very thorough picture of the creative process that Maibaum had gone through with various incarnations of the screenplay before the final shooting script. One element of controversy surrounding the pre-titles sequence of the film is whether or not George Lazenby improvised the line “This never happened to the other fellow” seemingly breaking the 4th wall talking into the camera onceTracy drives off leaving Bond alone on the beach after he had so dramatically saved her life. It would appear that Maibaum’s various screenplays have some variation of the line such as “This never happened before Double –O-Seven. Perhaps they ought to try again.” Also considered was “This never happened to Sean Connery.” For many years different conflicting variations of the story of how this line ended up being used in the film have been told. The most accepted version is that Lazenby himself ad-libbed the line and the director, Peter Hunt, decided to use it, but Helfenstein’s research seems to prove that the line had indeed been in the script. Whether or not Lazenby was meant to address the audience and look into the camera is still up for debate.

OHMSS was a film that involved a lot of risk. Not only were they introducing a new Bond with George Lazenby replacing Sean Connery in the title role, the producers were taking a risk promoting Peter Hunt to the director’s chair after serving as film editor on the previous films. This would be Hunt’s first time directing a film after his appeal to direct the previous Bond film, You Only Live Twice, had been rejected. Also, though OHMSS was an extraordinary story based on one of Fleming’s best novels, it would be a challenge to see if the audience would accept the deviation from formula that the story of OHMSS demanded. Bond would actually fall in love with a woman, propose marriage, and actually have a wedding. There would be genuine romance in a Bond film for the first time, which forced Hunt to remark that if anything had to be cut it would be action because the romance between Bond and Tracy was paramount to the story. There would be less reliance on gadgets and gimmicks that had become a staple to the audience despite the fact that there was little use of these gimmicks in Fleming’s source material. Also, the prospect of a downbeat emotional ending loomed as opposed to the previous high intensity climaxes, which audiences had grown to expect from the franchise. This time, the film would end on an emotional low with Bond’s wife being killed and a desperate Bond clutching onto her in vain imploring that “We have all the time in the world” in quiet yet stoic desperation.

Despite facing many obstacles, Peter Hunt achieved what many in the Bond fan community consider to be a high point in the film franchise. George Lazenby decided to quit the role of James Bond near the end of production refusing to sign a multi-film contract on advice from his manager / friend Ronan O’Rahilly who thought that Bond films would not survive and that George Lazenby should look for more anti-establishment oriented roles to cater to the then-current hippy trend. When this happened, EON relied heavily on his costar Diana Rigg to promote the film. Rigg’s strong performance in the film set a new standard for the role of the Bond girl. As Tracy, she is almost every bit Bond’s equal. She has her own fight scene that filmmakers incorporated into the role aware of her previous experience with action sequences in The Avengers television series. Indeed, many argue that it is Rigg not Lazenby who carries the film and earns the emotional depth that the film aims towards.

When Lazenby was reluctant to return to the studio for post-production work after deciding to quit the role of Bond, producer Harry Saltzman told him, “If you got hit by a truck tomorrow, I wouldn’t be happy about it, but I wouldn’t be out of business either.” Needless to say, there were and still remain many controversies regarding the release of this film, which Helfenstein does his best to shed light on. Lazenby refused to shave his beard for the Royal Premiere of the film in protest against the Bond producers who he now began to publicly criticize despite the fact that they had given him the very opportunity he had desperately asked of them. They had given him the role with practically no acting experience other than modeling and brief commercial work.

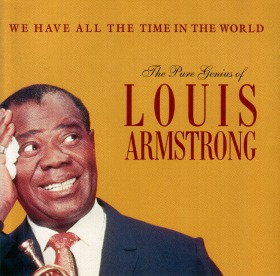

Helfenstein also details the work that John Barry put into creating the score of the film as well as in securing Louis Armstrong to record the song featured in the film, “We Have All the Time in the World.” Both John Barry and Peter Hunt convinced Cubby Broccoli to pay Louis Armstrong’s high asking fee, which would result in a beautiful rendition recorded merely two years before the legendary singer’s death. For the instrumental piece of the title song, Barry decided to write a riveting piece of music with a Moog synthesizer motif. Barry said he wanted the audience to forget they had Sean Connery when introducing the new Bond. He continued, “What I did instead was to over-emphasize everything that I’d done in the first few movies, and just go over the top to try and make the soundtrack strong. To do Bondian beyond Bondian.” Indeed, the music of John Barry really does play an instrumental part in establishing the tone of the movie as a Bond movie. His work on the soundtrack in the title song alone conveys a feeling of daring and resilience. During the romantic interludes between Bond and Tracy, Barry’s music permeates the film with the necessary depth and resonance.

One of the most revelatory sequences of the book occurs during the end where Helfenstein details some of Richard Maibaums initial treatments of the subsequent Bond film, Diamonds Are Forever. Maibaum had been unrelenting to the producers that the film not only should feature Bond seeking revenge on Blofeld for the murder of his wife Tracy but also that Peter Hunt should return to direct as well. In a personal letter to Cubby Broccoli, Maibaum implored, “Cubby, you may not like me saying this, but my heart is in the Bond series and I hope to hell you have a cutter as good as Peter Hunt. Peter may have become a monster as a director and I think he did a hell of a job with an idiot like Lazenby, but as an editor his contributions to the success of the films can’t be over emphasized. He made the films move.”

Unfortunately, Diamonds Are Forever, would not take Maibum’s suggestions. While United Artists were able to coax a reluctant Sean Connery back to the role of James Bond, the resulting film takes a light hearted tone and many regard it as a precursor to the Roger Moore era with its emphasis on humor, gadgets, and a Bond more prepared to deliver a quip than exact brutal revenge. Although Bond does square off against Blofeld in the film, the marriage to Tracy and the reason for Bond’s pursuit of Blofeld goes entirely unmentioned as if it never happened. Maibaum was able to insert a reference to Tracy in the 1981 Bond film, For Your Eyes Only, when Roger Moore’s James Bond visits Tracy’s grave during the pretitle sequence.

Charles Helfenstein’s book on the making of OHMSS is extremely comprehensive and fascinating for anyone interested in the world of James Bond. With interviews and extensive research, Helfenstein created the definitive document covering every aspect of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service from Fleming’s conception and inspirations behind the novel to every step of pre-production and screen treatments dating back to 1964 (5 years before the film debuted) to the casting, production, marketing, and release of the 1969 film. Everything a Bond fan could possibly want to investigate regarding OHMSS is here. If you are a Bond fan, you owe it to yourself to pick up this book.

Sources

- Fleming, Ian On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Jonathan Cape, 1963

- Helfenstein, Charles The Making of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Spies LLC, 2009

- On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, directed by Peter Hunt, 1969, EON.

- Listen to a fascinating interview with Charles Helfenstein for the James Bond Radio podcast here: http://jamesbondradio.com/the-making-of-on-her-majestys-secret-service-charles-helfenstein-interview-james-bond-radio-podcast-022/