In January of 1961 Ian Fleming retreated to his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica to write his 10th James Bond book. His previous novel, Thunderball, had been published despite Kevin McClory’s attempt to stop publication amidst accusations of plagiarism. Not surprisingly, Ian Fleming was in a dire physical and emotional state. He was no longer fit enough to ski at the Fleming family Christmas holiday retreat in St. Moritz. The previous year, Fleming had suffered a coronary forcing him to spend a month at a London clinic. His relationship with his wife Ann had become terribly fractured. Ann had never approved of Fleming’s Bond books because she found them distasteful and because her social circle also disapproved of them. Both Ian and Ann were also each engaged in affairs. Anne was seeing Hugh Gaitskell, a politician and Leader of the Labor Party while Ian was seeing Blanche Blackwell, mother of Chris Blackwell who would go on to become founder of Island Records and eventually become the owner of Fleming’s Goldeneye estate, a present day luxury resort. Some believe that Blanche was really the love of Ian Fleming’s life and that the character of Honeychile Rider from Dr. No may have been based upon her.

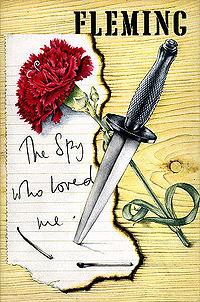

Fleming decided to take an entirely different approach with his next book, which would become The Spy Who Loved Me. Instead of writing it as a 3rd person omniscient narration has he had done with the previous novels, he decided to write in the 1st person from the perspective of a woman, Vivienne Michel, a French Canadian who had spent her late teenage years in England and whose tale was to focus on the various disappointments in her love life before the fateful night when James Bond saved her life. Bond in fact doesn’t appear until the novel has nearly ended. Instead, the reader is treated to the story of the life of this woman and how she came to be in the predicament that would require someone like James Bond to save her.

It must have been a considerable risk to Fleming to approach his book this way, and while contemporary reviews had almost universally panned The Spy Who Loved Me as a trashy attempt at a romance novel, I actually found it very enjoyable and I think the novel’s status as the literary black sheep in the Bond cannon deserves to be re-evaluated. After the novel had been poorly received, Fleming explained to his publisher that, “I had become increasingly surprised to find my thrillers, which were designed for an adult audience, being read in schools, and that young people were making a hero out of James Bond … So it crossed my mind to write a cautionary tale about Bond, to put the record straight in the minds particularly of younger readers … the experiment has obviously gone very much awry.”

The novel does indeed come across as a cautionary tale by the end of the story, but I also believe that Fleming had an even more personal aim in mind when writing this book. The novel opens up in a captivating way:

“I was running away. I was running away from England, from my childhood, from the winter, from a sequence of untidy, unattractive love-affairs, from the few sticks of furniture and jumble of overworn clothes that my London life had collected around me; and I was running away from drabness, fustiness, snobbery, the claustrophobia of close horizons and from my inability, although I am quite an attractive rat, to make headway in the rat-race. In fact, I was running away from almost everything except the law.”1.

Vivienne goes on to explain that she had been orphaned at early age and brought up by an Aunt in Quebec, who had sent her to “finishing school” in London to complete her transition into adulthood. She continues to reminisce about her past as she finds herself now an overnight caretaker in a secluded motel about to close for the winter in upstate New York near the Adirondacks. The music on the radio reminds her of the first of these “unattractive love-affairs” with an Oxford undergraduate named Derek. They would meet up weekly on Saturdays, spend the day together and end up at a cinema where Derek would encourage her to explore her sexuality doing almost everything short of the deed itself in a private box where they believed they wouldn’t be noticed. On the final Saturday of the summer before Derek would be off to return to school, he encourages her to complete the act of lovemaking in the theater box before being discovered by the owner of the theater and being thrown out in shame. Despite Vivienne’s utter humiliation, Derek continues to pressure her to have sex with him until she finally relents to do it behind some trees in a field. She felt as if she had to be “a good sport” about it and had been blind to the fact that Derek was looking to use her.

The setting of the cinema for Vivienne’s first sexual encounter was precisely how Ian Fleming lost his virginity according to Andrew Lycett’s biography. Derek cruelly sends Vivienne a letter letting her know that he was actively engaged to another woman over the entire course of their relationship and that his mother would disapprove of her status as a non-English woman necessitating the need to end their affair. Despite having her heart broken, Vivienne pulls herself together to become a journalist establishing a career similar to Fleming’s own journalism career at Reuters prior to his Intelligence service during the war. It is there that she meets a German man who offers her employment in his foreign news agency. Their professional relationship soon becomes physical, but as soon as Vivienne becomes pregnant, the German pays for her to travel to Switzerland to have an abortion and to terminate their relationship, which leaves her with the desire to “run away” as she had previously described.

After briefly reuniting with her Aunt in Quebec, Vivienne decides to drive on her Vespa scooter from New York to Florida to begin her life again, but decides to stop at a motel where these cagey managers offer her employment. The husband and wife who manage the place end up treating her cruelly, but since she wanted to make some money for her travels, she endured the husband’s advances. When a knock on the door comes during a storm, Vivienne unwittingly lets in the two gangsters sent by the owner to apparently burn down the place as part of an insurance fraud scam. They had intended to leave Vivienne’s corpse as evidence to imply that she started the fire to deflect any insinuations of arson. Their plans are kept secret from Vivienne while they subject her to beatings after her attempts at escape. Just when the hoodlums are about to rape Vivienne, James Bond shows up by coincidence after having a flat tire along the road by the motel.

Needless to say, Bond rescues her from the two gangsters after foiling their plan. The most controversial aspect of the book, however, involves Vivienne sleeping with Bond after being rescued. It may be a fair criticism to say that while Vivienne begins the narrative as a heroine of sorts, she ends up in the role of a typical damsel in distress, which may be where Fleming’s book falls a bit short. She does attempt to help Bond at several points, but Bond basically does most of the work dispatching the two criminals. Vivienne doesn’t linger too much on the graphic details of her sex with Bond, but I suppose there is enough there to make some readers feel as if the story ventures too far into the realm of erotica when most readers are accustomed to the Bond stories being thrillers. I think that her sleeping with Bond certainly fits within the context of Fleming’s story. After her two previous hallow sexual encounters, the point of her describing the act of making love to Bond was to contrast that experience with her previous ones. Even though she knew Bond wouldn’t commit to her beyond that single night, her experience with Bond was the first she had with a man who had been kind to her, a man who literally risked his own life to save hers. It might come off as a trite notion to get across in a novel and perhaps if Ian Fleming had been more creatively inspired, he could have done something even more original with the climax of this story, but as a reader I think it was bold to approach Bond in this way.

Perhaps the warning from the police captain to Vivienne may come across as even more trite to some readers, but it fits in with Fleming’s original intention of portraying Bond in a “cautionary” light. The captain tells Vivienne:

“’Keep away from all these men. They are not for you, whether they’re called James Bond or Sluggsy Morant. Both these men, and others like them, belong to a private jungle into which you’ve strayed for a few hours and from which you’ve escaped. So don’t go and get sweet dreams about the one or nightmares from the other. They’re just different people from the likes of you – a different species.’ Captain Stonor smiled, ‘Like hawks and doves . . .”1.

Indeed, when Vivienne first laid eyes on Bond, she thought he was another one of the gangsters there to torment her. She was frightened because she recognized a kind of cruelty in him. It is that very cruelty that Fleming wanted readers to see in Bond, which is why he tired of the notion of young school children reading his books praising James Bond as a hero. Fleming seemed to be tapping into the same themes that we explore today when we analyze our iconic fictional heroes. The notion that the same darkness may exist in the hero as it does in the villain is not a wholly original one, but I have to give credit to Fleming for at least attempting to explore this theme at a time when his readers wanted more of the same thriller material from him.

As Fleming himself admitted, the experiment of The Spy Who Loved Me failed commercially during the time of publication. The Times review said, “The novel lacks Mr. Fleming’s usual careful construction and must be written off as a disappointment.” Another critic wrote that the “author has reached an unprecedented low.”

Fleming himself requested that the book not be released in paperback in the UK and that there be no further printings of it. When Fleming sold the film rights to his Bond series to EON, he included a stipulation that only the title of The Spy Who Loved Me be used and that nothing of the plot should appear in any film adaptation of the book. EON did eventually release The Spy Who Loved Me as a film in 1977 starring Roger Moore. It is regarded as one of Moore’s best films, and the plot of the film shares absolutely nothing with the plot of the Fleming novel. Instead, Bond partners with a female Russian counterpart spy to take down a maniacal villain intent on destroying the planet in order to establish his own underwater city. As one might guess, the film requires a bit of suspension of disbelief, but it’s actually quite entertaining.

Fleming himself may have wished to discard his novel of The Spy Who Loved Me, but I think the book deserves to be re-evaluated not only by Bond fans but as a work of literature. Vivienne Michel’s story is an engaging portrait of a woman’s coming of age during a time before the woman’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s. It was written during a time when the notion of a woman exploring her sexuality was still considered taboo. Today, we have an entire genre of romance and erotica novels that have reached a level mainstream acceptance and financial success. One needs only to think about the success of Fifty Shades of Grey to see how much things have changed since The Spy Who Loved Me was published in 1962. One can only wonder how far Fleming would have taken this “experiment” with James Bond had this attempt met with any measure of success. I for one wish he had the chance to experiment even more with Bond. I think if we re-examine this novel today, many might see that perhaps Fleming’s “experiment” hadn’t failed after all.

Sources:

- Fleming, Ian The Spy Who Loved Me. Jonathan Cape, 1962

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Spy_Who_Loved_Me_%28novel%29#cite_note-FOOTNOTEChancellor200511-11

- http://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/oct/26/when-ian-fleming-tried-to-escape-james-bond

- http://literary007.com/2014/08/20/the-three-ages-of-bond-part-3-suffering-bond-1961-1964/

- http://spartacus-educational.com/WNblackwell.htm

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Gaitskell

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chris_Blackwell

Love it Fantastic!

LikeLike

Great post. I agree that the book isn’t quite the failed experiement it’s purported to be. I’m not sure that the 1977 film has nothing of the book, though – Horror’s capped teeth may have inspired Jaws, and there’s something of Sluggsy in the film’s Sandor too. Also, I do wonder whether Fleming’s book owes less to romantic fiction than American crime fiction, of which Fleming was an aficionando. I explored these points in my post on the novel:

http://jamesbondmemes.blogspot.co.uk/2014/02/failed-experiment-or-misunderstood.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your kind words, Edward. I enjoyed reading your take on the novel as well.

LikeLike

[…] The Spy Who Loved Me – A Look at Ian Fleming’s Discarded Bond Novel […]

LikeLike